Basic Scenario Prep

This post is actually a more detailed response to a question on Reddit about prepping for a Call of Cthulhu scenario. Unfortunately, the comment limitations forced me to post an abbreviated response, so this is the more detailed post. It’s still a little rough, and far from comprehensive, but these are the basics of a method for prepping to run an investigative scenario. It can be extremely helpful for newer Keepers, as well as help reveal potential pitfalls in published scenarios before running them.

This applies primarily to prepping pre-made/published scenarios (including sandbox campaigns), but most of this can still apply to more free-form or improvised scenarios to one extent or another.

- Read through the scenario to get some basic familiarity.

- Identify the Fail-State. (Or if you like: Identify the Impending Doom)

- What happens if the investigators fail – or if they don’t become involved at all?

- This really helps understand what’s going on behind the scenes and is very useful when the investigators get sidetracked and you need to instill a sense of urgency.

- For many scenarios this is fairly obvious – something like the cult summons a Great Old One, and so the apocalypse begins. But it’s amazing how many scenarios don’t really go into this – even popular ones like The Haunting, Paper Chase, etc.

- What does success look like? What do the investigators need to accomplish to end the scenario successfully?

- I’ve actually had scenarios flounder at the end because we couldn’t decide where to actually end things – this helps with that.

- More importantly, it lets you determine one crucial thing…

- What conclusion do the players need to reach in order for the investigators to be successful?

- In the Masks of Nyarlathotep Peru Prologue, for example, the investigators need to return a gold artifact to its place in a pyramid in order to end the scenario successfully. So the players need to reach the conclusion that the artifact must be returned to the pyramid.

- Understanding what conclusion the players must reach helps you identify which clues are really important and recognize holes in the scenario that could cause the investigation to stall.

- Identify Locations & Characters. Make a list of all the locations and characters in the scenario. Also list any important artifacts, tomes, etc.

- If you’re not sure if you should include something in these lists, ask yourself this question: Can this place/person/thing provide the investigators/players with information that will help them reach the conclusion or help them find other clues? If so, add it to the list.

- Build Clues (Identify, Categorize, Organize, Fill Holes)

- I’ve been meaning to write a blog post on this subject, but here’s the quick version.

- This step is arguably the most central to how I prep for investigative scenarios, and in some ways it’s also what’s different about how I prep. Essentially, you are going to re-read the entire scenario and write down every clue you can find. Then you’re going to categorize and organize them.

- Distinguish between clues and their sources. A translation of an ancient tome is not a clue, but the information contained within it likely includes many clues.

- Treat clues as discrete, individual pieces of information – and write them that way. Write each clue as its own brief phrase or sentence, separate from other clues. If it’s remotely conceivable that the investigators could learn one piece of information but not the other, then they should be two separate clues.

- This will likely result in a long list of clues – I had nearly 60 clues for the Masks Peru Prologue.

- Categorize each clue as either Core or Supporting.

- Core clues either lead to more sources of clues (locations, characters, etc.) or are vital to the players reaching the correct conclusion. Keep in mind that the players need not understand the conclusion to reach it. For example, the players don’t need to understand why returning the golden artifact to the Peruvian pyramid will resolve thing, as long as they figure out that it’s necessary.

- Supporting clues are everything else. They don’t lead to new sources and are not critical to reaching the correct conclusion, but they do provide more information that explains things. These are the clues that help the players understand what’s going on. They might even help players reach the correct conclusion early, but they’re not necessary.

- Organize your clues by the location(s) where they may be found. This can overlap into the next couple of steps if clues could be available only at certain times (in specific encounters). Also consider that clues can be static or floating.

- If a clue can only logically be obtained in specific locations or encounters, then it is a static clue.

- If a clue could easily be assigned to multiple locations/encounters, consider making it a floating clue. The location of floating clues is not determined ahead of time, instead the Keeper includes it in whichever encounter makes the most sense during play (or whenever the investigators need some new information to move things along). For example, the Master’s Last Will and Testament contains some important clues, but it could reasonably be found in several places throughout the house (or even elsewhere). The Keeper waits until the investigation has progressed a while, then when the investigators search the next possible location of the Will, the Keeper provides it.

- Make sure that there are sufficient Core Clues to lead players to the correct conclusion. Also make sure that there is a clear path (or paths) lead to each of your Core Clues, locations, and encounters. Consider how the investigators would need to interact with each potential source of clues in order to obtain all of the Core Clues. You may find some holes in your scenario that you need to fill.

- Holes that can cause the investigation to stall are often caused by the players needing information pointing to a specific location or source, but there is either no actual clue providing that information, or the action necessary to reveal that clue is not intuitive. Making a Clue Map can help identify these gaps.

- For example, in Dead Man Stomp, the players need to end up going to a funeral the next day (where they receive more clues), and the latest version of the scenario makes it very clear that the Keeper needs to get them to understand the funeral is important. However, there are perhaps two clues that lead to the funeral, and there is very little that would even lead to the investigators receiving those clues. Understanding the holes in the scenario from this perspective makes it obvious why so many Keepers run into challenges when running it.

- Identify Encounters & Opposition

- Working through your list of locations, identify the encounters that could occur at each. Some locations may only have a single encounter, while others could have several. For each encounter, identify what opposition exists. What do the investigators have to overcome to accomplish their goal(s) in the encounter (obtain the clues or items, get assistance, escape, etc.)? In other words, what rolls do they need to make and against what? (This bit could vary somewhat depending on what system you’re using and your preferred style of play.) Some encounters may not have any opposition, if a helpful character or other source of information is simply providing clues now that the investigators have located it.

- Encounter Summaries

- Write a brief summary of each encounter, including:

- Encounter Location

- Character(s) introduced & character(s) present

- Core and Supporting clues available in the encounter

- Other relevant items, artifacts, tomes, etc. found in the encounter

- Opposition that may be faced

- Handouts or props that may be found in the encounter

- Write a brief summary of each encounter, including:

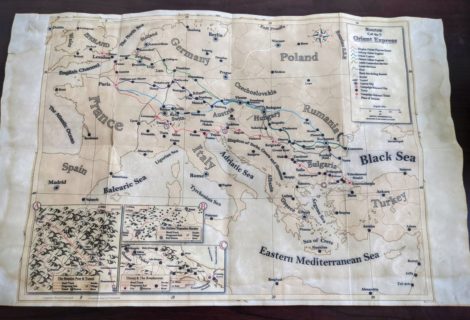

- Clue & Encounter Maps

- Optional but very helpful (especially for longer/more involved scenarios), make Encounter and Clue Maps.

- Encounter Map simply shows how encounters lead to one another (determined by the clues provided by each).

- Group encounters at the same location together. Use arrows to lead from one encounter to others. If you have multiple pages, consider color-coding by location. Note which encounters are optional. Consider using different markings to show which pathways are based on Core Clues and which are Supporting.

- Clue Maps are more involved, but this is where everything can come together.

- Shows how encounters and investigator actions lead to clues, and how those clues lead to other locations and encounters. Full map includes all clues and encounters, but I also find it useful to make a second Clue Map with just the Core Clues and how they lead the players to the correct conclusion.

- I’ll post examples from my Masks Peru prep, as that will probably be more helpful than trying to explain. Here’s a PDF of those clue and encounter maps.

- Cards & Props

- Figure out what props you want and get them together.

- I’m working on a method for playing CoC scenarios with my family that includes making cards for clues, locations, and characters. It’s been extremely successful so far and helps avoid some common issues that can come up in investigative games. So one of my last steps is to make these cards – along with some blank ones I can use if unexpected stuff comes up in play.

What do you use to make the clue / encounter maps? Do you have a template I could borrow?